Published: 31 July 2019

The desire to fit in is directly opposed to the desire to stand out. This is one of the essential human conflicts. We all want attention, to be noticed and acknowledged. To see ourselves reflected in other people’s eyes is a fundamental way that we confirm we exist.

Watch any small child and the demands they make on parental attention. “See me!”, “Hear me!”, “Touch me!”, “Feed me!” are among our earliest commands. It is a banal observation that children who are denied positive attention will seek negative attention in preference to none at all.

Loneliness is an expression of how existential the desire for people to see us and respond to us actually is. We feel invisible when we move through crowds of strangers who pay us no mind. This can be a pleasant experience if it is rare, but for many in our community it fills them with despair and a sense of how utterly unimportant they are. They, perhaps, ‘fit in’ too seamlessly, to the point where they no longer appear to actually have a separate existence, or not one worth noticing anyway.

Women, it seems to me, try hard to fit in because they are likely to be punished if they seek to stand out. Women are praised, particularly when young, for being modest, quiet and well behaved. Indeed, the term ‘well behaved’ is all about fitting in. A person who earns such an epithet obeys the conventions of social intercourse. They comply with what is expected, they behave as they should. As girls grow into women, ‘well behaved’ morphs into ‘ladylike’. The suffix of the term gives the clue. Women aspire to be ‘like’ ladies. They must distort their actual selves to fit that narrow, rather prim description. The idea of being a ‘lady’ is the human equivalent of Cinderella’s glass slipper. It is fragile, transparent, impossibly small and cripplingly uncomfortable. Unlike good girl Cinders, real human women are ugly sisters, forced to cut off parts of themselves to fit the acceptable stereotype.

None of us are immune to that pressure. When I was young, I sought endlessly to be the kind of good girl I saw around me. The girls who were neat and tidy, who always had their desks and pencil cases in good order. The girls who had always done their homework and were the first to be nominated as monitor, class captain and prefect. I never achieved any of those lofty goals. No matter how much I berated myself, no matter how much I was berated by others for being a show-off, pushy, and talking-too much (it was a constant in my school reports), I could not defeat my equal and opposite desire to stand out.

Nor my careless, messy, slapdash approach to neatness and tidiness. I did not fit in. My image of myself as a child is that I annoyed and irritated people. I was not what a little 1960s girl should be and I mourned my lack of likeability. I hated primary school. I was a bookish, long-word-using, noisy, cack-handed, un-co child in a world that worshipped sport, maths and conformity. My lifelong antipathy to team sport of any kind – but especially that niminy-piminy girl’s game netball – was formed at the hands of a multitude of good girls who took pleasure in excluding me for my inability to obey the rules or catch a ball. Good girls are not necessarily nice girls. The mental contortions they have made to make themselves fit in are not without cost and they revenge that pain, I think on those who either will not or cannot make the same sacrifices. I wasn’t without friends, but we were clearly the leftovers and misfits, clinging together for comfort. I was the smallest girl in the class, looking years younger than I was. One of my closest friends was the tallest in the whole school. She looked like a fully grown woman. What an odd, ill-fitting pair we must have made. In high school – a place where I felt a much greater sense of belonging – I solved my dilemma by meeting up with a bookish outsider like myself. Our friendship (it continues to this day) not only nurtured us, it made us less threatening. We were allowed to hover around the edges of the cool group because we posed no threat to anyone else. Friendship is often provisional and transactional among those who are desperate to fit in. Do you help me feel accepted? Or do you make me stick out awkwardly even more? Those who stand out live in dread of being cast out. This fear can last a lifetime.

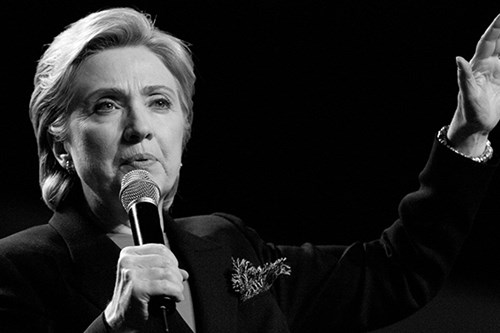

Even as adult women the desire to fit in remains self-protective. We have watched the women who are determined to stand out and we have seen what happens to them. US President Donald Trump and his supporters still chant ‘lock her up’ at the mention of Hillary Clinton’s name. Almost 25% of the handful of women who have led countries over the last few years have been accused of corruption, impeached for corruption or jailed for corruption. Our lone female Prime Minister was not immune and investigated for a so-called slush fund from her time as a young lawyer. The scandal faded away completely once she lost office. While she led us, however, we watched her being eviscerated for her effrontery on a daily basis. And we got the message – by refusing to fit in, Gillard put herself beyond the pale. In 2016, many Americans stayed away from the ballot box entirely and among those who didn’t, a shameful 52% of white women voted for a pussy-grabbing misogynist rather than for a woman. In the face of the relentless barrage of scorn and abuse aimed at the only serious female candidate for the Presidency so far, white women allowed their desire to ‘fit in’ to overwhelm everything else. Perhaps that was why, to their credit, American women of colour had no such qualms and supported Clinton so comprehensively. They gave up any hope of fitting in long ago.

Good girls are not necessarily nice girls. The mental contortions they have made to make themselves fit in are not without cost and they revenge that pain, I think, on those who either will not or cannot make the same sacrifices.

Former Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, Image Credit: Greens MPs

One of the most common explanations otherwise reasonable people gave for voting for a kleptocrat like Trump was Hillary Clinton’s lack of ‘likeability’. Loud were the cries of “I’d love a woman President, just not this woman.” Really? It seems we easily love a loyal female 2IC – Clinton herself had a 69% approval rating and was the most popular woman in the country when she finished her term as President Obama’s Secretary of State. Julie Bishop was a much admired deputy leader of the Liberal Party and foreign minister but she could muster only 11 party room votes when she stood for the top job. Julia Gillard was a beloved Deputy PM who became a figure of vicious hatred when she toppled – as so many men have done before and since – her Prime Minister. The current crop of Democrat women who have declared their candidacy for the 2020 US Presidential campaign are already starting to hear the word ‘unlikable’ whispered in their ears. We do not like a woman who stands out. Perhaps this is why women are so quick to deflect compliments and spread any praise onto others. They sense the danger that accompanies any implication that they deserve to be singled out and noticed.

Interestingly, American author and research Professor Brene Brown believes the opposite to ‘fitting in’ is not standing out, but ‘belonging’. She believes that what we really yearn for as we contort and discipline ourselves to be more like others is to feel we belong. We are herd animals, after all, and our survival is dependent on our connection with one another. She also argues that the more we try to ‘fit in’ the less likely we are to feel we truly belong.

Hillary Clinton, Photographer: Brett Weinstein flic.kr/nrbelex

Indeed, as our female political leaders have shown, it is hard to belong as a woman in a male dominated world. I have watched young, forthright women experience this lack of belonging when they face off with older, often conservative men on panels or on social media. Many of the men take instant umbrage if their young female opponent voices her disagreement. Perhaps it is unconscious, but men, particularly older men, were brought up to expect all women to defer to them, but especially those who are young. When a young woman or a woman of colour insists on her right to an opinion, she is refusing to ‘fit in’ with a convention that has existed for centuries. Her reward, as Yassmin Abdel-Magied discovered after posting a seven word anti-war tweet on Anzac Day, is to risk being cast out. Abdel-Magied was hounded out of the country.

Image Credit: Lindsey LaMont

This lack of being able to feel we belong may be why Australia has one of the most gender-segregated workforces in the western world. Exhibit A is the Federal Liberal Party where we have watched senior women leave the parliament in droves when overlooked for promotion or disendorsed for their seat in favour of a man. Worse, many have left complaining vigorously about a culture of misogynistic bullying. Women such as Julie Bishop, Kelly O’Dwyer and Julia Banks have tried hard to ‘fit in’ with the parliamentary party that best reflected their worldview only to find all their efforts in vain. One of the ways they have had to try and ‘fit in’ was to disavow feminism. This is annoying for feminists like me, of course, but I believe it is much worse for them.

Feminism exists because many women have understood that they would never be fully accepted by men and that their efforts to ‘fit in’ to the small spaces they were allowed to occupy under patriarchy were self-defeating. They gave up trying and formed their own outspoken female support group. They formed their own club, or friendship group, to which they could truly belong – despite ructions, debate and differences of opinion. Feminism has no interest in glass slippers or ‘fitting in’. At its best, it has no interest in conformity or obeying the rules. It exists to support women become more fully themselves, to assert their full and equal humanity, to insist ultimately that women can belong to human society just as they are, just as much as any man.

Jane Caro

Jane Caro is a Walkley Award winning Australian columnist, author, novelist, broadcaster, advertising writer, documentary maker, feminist and social commentator. She has published twelve books, including three novels Just a Girl, Just a Queen and Just Flesh & Blood, a trilogy on Elizabeth Tudor, and a memoir Plain Speaking Jane. Caro appears frequently on The Drum, Sunrise and Weekend Sunrise and has created and presented four documentary series for ABC Compass. She and Catherine Fox present a popular podcast with Podcast One, Austereo Women With Clout. Caro also writes regular columns in Sunday Life and Leadership Matters.

You May Also Like

Behind the Scenes

Our Behind the Scenes series takes you on an exclusive journey into the heart of QPAC, where the magic of the stage comes to life.

Projects and Events

QPAC is a creative hub where communities come together to celebrate, learn, and grow through the transformative power of the arts.

Digital Stage

On-demand performances, live streams and behind-the-scenes.

Support

Support QPAC to help nurture and celebrate Queensland's rich artistic heritage while fostering innovation and creativity for the future.